Jump Cuts – Julian Grant

- Regular

- $22.99

- Sale

- $22.99

- Regular

- Unit Price

- per

If you are interested in a part set for a performance, please contact us.

Composer: Julian Grant

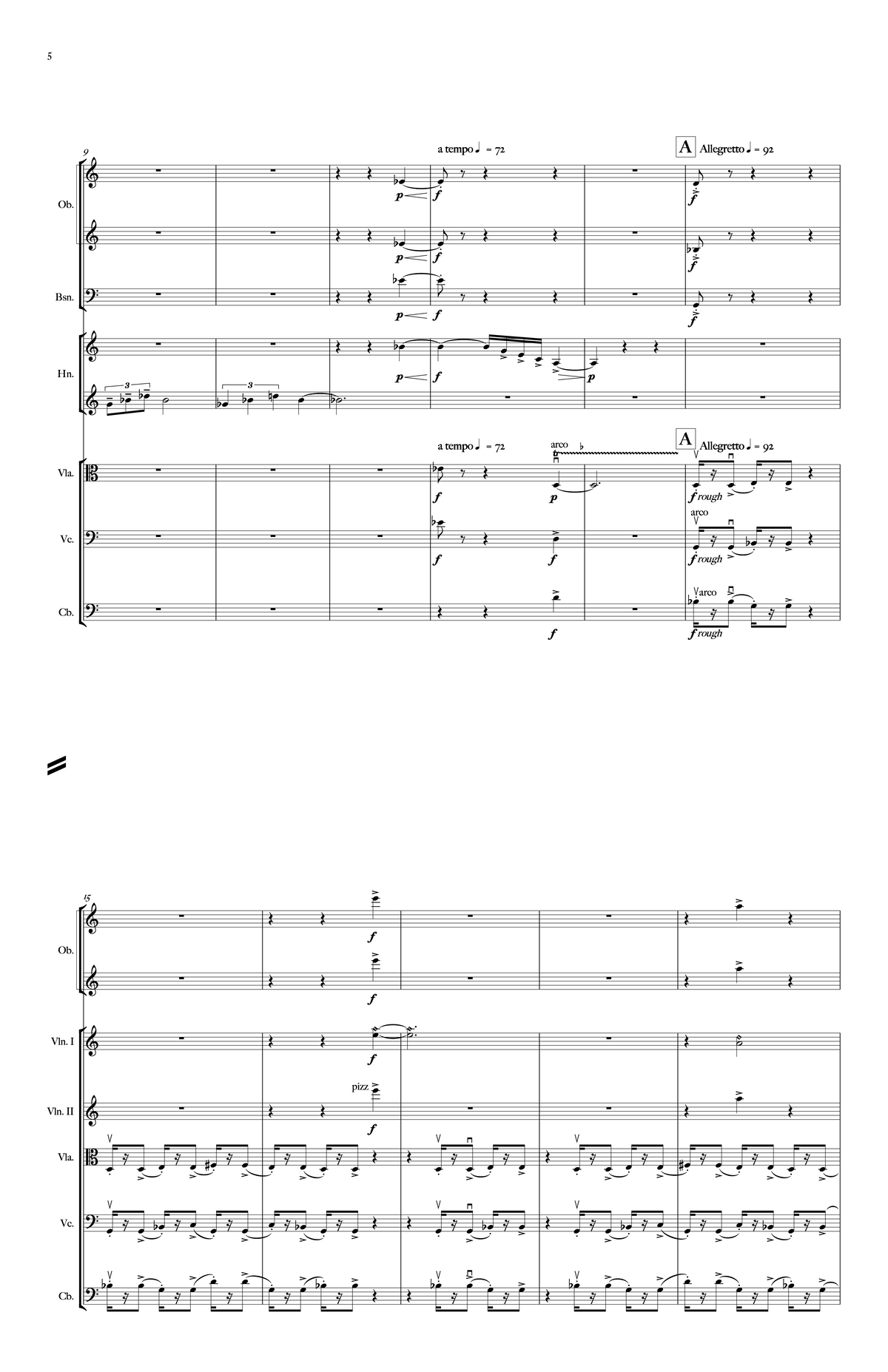

Instrumentation: small orchestra (2 oboes, bassoon, 2 horns, strings)

Duration: Approx. 16 minutes

Date Written: 2019

Additional information:

My commission from Manitoba Chamber Orchestra came with a very specific brief: it should of an agreed length and be written for a reduced chamber orchestra - strings, two oboes, two horns and a bassoon. This is standard scoring for the dawn of the symphonic repertoire - the very earliest symphonies of Mozart and Haydn, for example. I did think of writing a three movement homage to those early symphonies, but that is territory that was comprehensively covered by the 20th century neoclassicists - and Stravinsky’s legacy loomed too large.

My usual workplace is in the opera house, though I have been dabbling more and more on the orchestral scene recently. Thus, it was no surprise that my 12 minute curfew conjured up an iconic piece: Rossini’s ‘William Tell’ overture. This consists of four very different scenes, an elegy, a storm, a pastoral idyll and the military galop immortalized by the Lone Ranger. But my sketches for Jump Cuts did not start with a narrative or a scene (my usual practice) but with snippets that oddly refused to coalesce. At the same time, on late night TV, I had caught a re-run of an old classic: Jean Luc Godard’s ‘Breathless’ (with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, the 1960’s precursor of all the cool gangster flicks) and the germ of this piece was born. I stopped trying to force what seemed like irreconcilable elements together (a process known as consilience, according to a physicist friend), and studied how Godard pioneered the idea of a jump cut - sequential shots of the same subject taken from different angles, with no transition, or an abrupt segue from one scene to another.

So instead of Rossini’s four distinct scenes, my piece darts around from mood to mood, tempo to tempo, as if the fabric is cut by scissors. The initial idea, a call of two horns, one noisy, and one muted, as if from a distance, is thrown around in a variety of guises, culminating in an unruly procession, where the violins fail to get into sync. Do please make up your own narrative, enjoy the unexpected scenes and landscapes that unfold, and prepare for a few jolts.

By the way, I am told by a film director, that my use of the term ‘jump cut’ is not quite accurate, it should in fact be a ‘smash cut’ (a non-sequitur shot from one unrelated thing to another), but I feel my piece jumps rather than smashes, so forgive the technical inaccuracy for the sake of poetry.

The piece was completed at the Hermitage Artists Retreat, Florida and commissioned by the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra. Jump Cuts is dedicated to the memory of my wise and wonderful stepfather, Alan Biffen (1925-2019)

Es ist genug (It is enough) was written by Franz Joachim Burmeister (1633-72) and set to music by Johann Rudolf Ahle (1625-73), who was a predecessor of J.S. Bach’s at Mühlhausen. It was first published in 1662, as a vocal piece in six parts (2 sopranos, alto, 2 tenors, bass). The melody has caused comment, as the first four rising notes are all whole tones, which overshoots the customary major scale and outlines the tritone, or diabolus in musica. This, in earlier times, was a forbidden dissonance, and has since been used in Western music of all periods, to convey unease and disruption. Bach took the last verse of Es ist genug and harmonized Ahle’s melody for four voices as the final chorale of his cantata for the 24th Sunday after Trinity, O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort (O eternity, you word of thunder), BWV 60. This was one of the earliest of the more than 200 sacred cantatas that Bach composed during his Leipzig period: it was first performed on 7 November 1723. Compared to Ahle’s simple harmonies, Bach’s are unexpected, with, at one point, a sliding chromatic bass that very nearly implies the musical impressionism of Debussy, or even some floating jazz chords. The congregation would have known the chorale melodies and been expected to join in at the conclusion of the service, though whether they would have managed Bach’s harmonization is a matter for conjecture. There is a satisfying symmetry in Ahle’s melody, which balances the first four ascending whole tones with four final, almost identical descending pitches. This descending figure looms large in subsequent musical literature, becoming a symbol of farewell. The last three notes (like a horn-call, or ‘Three Blind Mice’) surface as the opening gesture in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 26 in Eb major op. 81a ‘Les adieux’ with the word ‘lebewohl’ (farewell) spelled out, each syllable attached to a note. Later, Mahler was to use and abuse these three notes to terrifying effect in the first movement of his Ninth symphony. Aficionados of twentieth century orchestral repertoire will know the whole chorale (in Bach’s version) as it appears in the final section of Berg’s Violin concerto of 1935. There is also a later set of variations on the chorale for viola and string orchestra (1986) by the Russian composer Edison Denisov (1929-96), and an orchestral piece by Magnus Lindberg (2002).

What struck me, after getting over being completely intimidated by all these illustrious predecessors, was the power of the cadences, the punctuation points that bring the music home, or not, at the end of each phrase. There is a colossal certainty about them, as if to bolster Lutheran faith and banish all doubt. I found them impressive and impassive, particularly from a 21st century vantage point, where musical language offer no such certainty. Hence I emphasize these cadences, and cast them as mighty pillars thatstand out in a sea of ambiguity. Is it enough? Perhaps it is…..was commissioned expressly to precede a performance of the Berg concerto, and uses exactly the same orchestra as the Berg. This meditation includes both Ahle and Bach’s versions of the chorale, albeit split up and in contrasting tonalities. Bach’s inner parts have a life of their own, and dominate the piece as it proceeds, blossoming into some long breathed, almost symphonic melodies. The ten minute piece concludes with a hard won affirmation of the final cadence and weaves the final notes of the chorale into an extended farewell.

© Julian Grant 2016